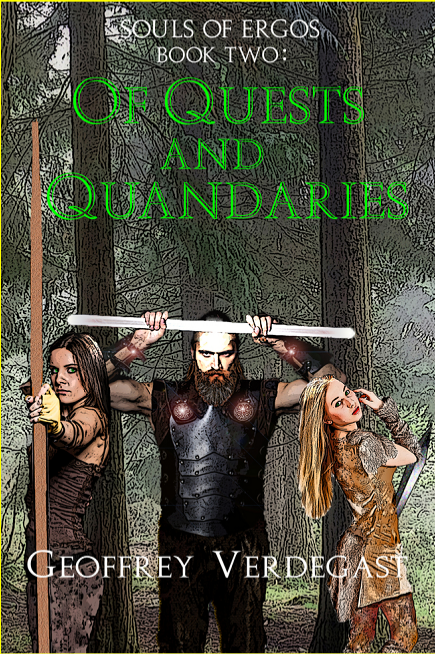

Please sample an excerpt below:

From Chapter Twelve:

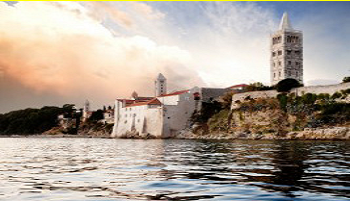

At last Orlahn was within their sights. Of course, there still lay one league of restless sea-water between them and the isle, but after day upon day of brisk travel -- and night over night of broken sleep -- Balgor and Gralok stood one lengthy swim or one short sail from their goal.

"What say you, Gralok? How are your raft-fashioning skills?"

"Never before," said Gralok. "Might we not signal them somehow, to send a vessel for us?"

Balgor laughed. "Bad enough that we come to twist their arms for a Soork that may or may not be in their possession, but we also have the temerity to insist that they bring us to their doorstep to hear our plea?"

"Are they not our countrymen?"

"In long-ago blood, perhaps. But these Orlahnians have evolved in their politics to a degree that differs in several key fashions from those of our mainland kin."

"Aye, but surely they despise the NuRacs as we do. I recall you telling me that some of them were imprisoned alongside you in QieLahr."

"They were. But in far fewer number than the rest of us."

"Is this provocative to you? Perhaps those who were captured were the only ones who had left the safety of their isle and had come ashore."

"Oh, I am sure of that."

"Then what?"

Balgor squinted at the far-off land mass, half-obscured by fog. "The Orlahnians were the first and the last to trade with the NuRacs, years back, when the NuRacs were more benign. These northern lands were the first places to feel the pinch of NuRac encroachment. I cannot help but to puzzle why Orlahn was spared when they turned aggressive and began taking Ergosian territory for their own."

Gralok stared out across the waters. "Foremost, because the NuRacs have no maritime skills. The Orlahnians do. Very good ones, I am told."

Balgor smiled. "What manner of clodpate am I, my friend, to not realise that the most obvious answer is usually the correct one?"

"I will tell you," said Gralok, "but, I warn you, the truth may be painful."

For a while they strode the rocky shoreline, east and west, hoping to come across a dock or quay -- and perhaps a small shuttle moored to it for messengers, visitors, or for returning Orlahnian foragers to use. Initially, they found none. Lacking this success, Balgor commenced, then, to scrounge for a handful of seaworthy logs, and the hemps and grasses with which to bind them. Gralok followed suit.

In time, and with the aid of the small war-axe they'd brought along, they'd hewn six suitable pieces of timber to comparable lengths. Then, with their impromptu twine -- and with the bit of rope that had been included in their packs -- they were able to begin fashioning. Balgor chose the lightest, most buoyant woods for the project, particularly several partially-rotted trunks, for he'd determined that with his and Gralok's combined hefts they would need to displace as little water as possible to stay afloat. Decaying wood weighed less, and would therefore trim a few grams in the right direction. And although he knew that the rotted lengths would waterlog more quickly than would haler ones, he believed that they would nevertheless serve nicely for two short jaunts -- one to Orlahn, one from.

Another little gem of sailing ad hockery that he'd learned from one of the more knowledgeable fishermen in the rebel camp was to employ longer pieces of timber in the construction -- longer than what seemed sensible -- as he was assured that this would not only spread the load across a greater surface, but it would make the raft easier to manoeuvre. Neither man being at all nautical, they truly did not know what to expect once asea; but they were not the kind to shrink from new challenge, especially when the realm stood in the balance.

For the sake of convenience, they built the raft while standing knee-deep in the water, even as many an ornery comber jostled their efforts with irking regularity. The bobbing logs, however, weren't tossed to quite the extreme that they might have been -- and in fact rode the surface rather splendidly -- which made for a less harrowing process in securing them one to the other. And eventually, beyond a few false starts, one failed twine, and a peck of re-work, they had before them a not-so-handsome but workable conveyance for bringing them to the people of Orlahn.

Oars were next, and they spent an inordinate time in search of suitable paddle-wood. Nothing at hand seemed broad enough to provide for efficient stroking, and neither man understandably wished to hack and hew at a large trunk in hopes of netting the wide, sturdy, slim-handled accessory that they desired. At end, however, they were forced to do just that. Driving both the axe and their daggers into what was deemed the most promising bole, with considerable effort they were able to wedge in and split it lengthwise, which yielded them a radial pair, each with one flat side. Then, going to work on the barked portions of the halves, they whittled and carved and excised until they had resected enough to result in two passable oars.

Petulant in their success, within minutes of completion they redonned their packs, refitted themselves, and made ready to fulfil their mission. Leaving solidity and sure-footed comfort behind, they pushed off with the confidence of fools, hopeful that their amateur construct would be sturdy enough to see them through.

Far from a blustery day, upon the water it soon became a different story. Once they were fully committed the wind gained advantage, and at times it was more than they could manage merely to balance the craft and keep its heading straight. But they were strong men, and persistent, and after escaping the influence of the shore-bound breakers it became easier to maintain their bearing, windy or not. One man paddling from the port side, and the other, from starboard, they proceeded without falter or incident toward the misty isle ahead.

At roughly two kilometres out, however, near the half-way point, something in the water caught Balgor's eye. In silhouette, twenty metres from the bow, there appeared an object in jut from the surface. As quickly as he focused on it, it submerged and was replaced by two similar juts ten and fifteen metres to starboard. He called Gralok's attention to the phenomenon, but he, of course, had seen nothing. The pair of silhouettes having slipped beneath the water no less swiftly than the first, it was only when all three bobbed up simultaneously a few seconds later that each man saw what the other did.

"Men or fish?" asked Gralok.

"I know not. My only hope is that they are one or the other, and not something that is neither man nor fish."

"What could be neither man nor fish? Sea-faring vrohdas?"

"Jest if you wish," said the realmson. "But I like it not."

They rowed on with a bit less verve in their strokes, instead channelling that cautious percentage of energy into a jerky paranoia of glances for additional signs of unwanted company.

"Why do you tap on the raft?" asked Balgor.

"It is not I," said Gralok.

Balgor touched the wood beneath him. There was definitely a vibrative sensation to it, vibrative as when mice burrowed and chewed within the walls of one's abode. Had they unknowingly chosen a log that had been host to a rodent hovel? An insect nest? No, he knew that this couldn't be; the former would have fled their pulpy sanctuary at the first few axe hacks, and the latter would surely have swarmed in defence of theirs. Yet, if not these explanations, then what?

They hadn't long to ponder. Within the minute, the outer starboard log detached from their craft and fell away in drift. Balgor grabbed for it, but his effort returned him nothing save a severed strand of twine.

"Blasted saboteurs!" cried Balgor. "They seek to undo us! Quickly, Gralok -- your blade!"

Both men drew and began jabbing their daggers through the joints and alongside the vessel, hoping to dissuade their assailants from disabling them further. Whether it was man or beast below, surely they bled, and randomly thrusted steel was the best and most that the rafters could offer in countermeasure.

This worked, temporarily. But, so busied with keeping their log-boat whole, this left no one to paddle it; and when they settled on one man defending and one man rowing, their harrowers counteracted in thwart. Apparently gleaning the position of the oar-man from underneath, said clever beings fixed upon the lashings beneath him and continued to dismantle. The rafters, frustrated by their disadvantage, rowed and stabbed, stabbed and rowed -- neither with calm or focus -- until the very moment that their submarine saboteurs finally succeeded in unseaming the construct completely.

Suddenly amid a loosed muddle of logs, each drifting in its own direction, Balgor and Gralok quickly spilled into the drink. Floundering in the bracing chill, they lashed at empty ocean, thrusting their blades wildly in a long-shot hope of crippling a far more dextrous enemy. Finding their backpacks not terribly buoyant, both men were too limited in their mobility to simultaneously fend and tread water, and it was no significant while before they began to tire. Dark, shadowy forms darted confidently around them, deliberately drawing their fruitless exertions and draining them further, and before long neither man was in condition to retaliate. And of the little fight that remained in them, this was easily expended with a bit of body-buffeting knockabout, courtesy of their still-faceless assailants.

"What say you, Gralok? How are your raft-fashioning skills?"

"Never before," said Gralok. "Might we not signal them somehow, to send a vessel for us?"

Balgor laughed. "Bad enough that we come to twist their arms for a Soork that may or may not be in their possession, but we also have the temerity to insist that they bring us to their doorstep to hear our plea?"

"Are they not our countrymen?"

"In long-ago blood, perhaps. But these Orlahnians have evolved in their politics to a degree that differs in several key fashions from those of our mainland kin."

"Aye, but surely they despise the NuRacs as we do. I recall you telling me that some of them were imprisoned alongside you in QieLahr."

"They were. But in far fewer number than the rest of us."

"Is this provocative to you? Perhaps those who were captured were the only ones who had left the safety of their isle and had come ashore."

"Oh, I am sure of that."

"Then what?"

Balgor squinted at the far-off land mass, half-obscured by fog. "The Orlahnians were the first and the last to trade with the NuRacs, years back, when the NuRacs were more benign. These northern lands were the first places to feel the pinch of NuRac encroachment. I cannot help but to puzzle why Orlahn was spared when they turned aggressive and began taking Ergosian territory for their own."

Gralok stared out across the waters. "Foremost, because the NuRacs have no maritime skills. The Orlahnians do. Very good ones, I am told."

Balgor smiled. "What manner of clodpate am I, my friend, to not realise that the most obvious answer is usually the correct one?"

"I will tell you," said Gralok, "but, I warn you, the truth may be painful."

For a while they strode the rocky shoreline, east and west, hoping to come across a dock or quay -- and perhaps a small shuttle moored to it for messengers, visitors, or for returning Orlahnian foragers to use. Initially, they found none. Lacking this success, Balgor commenced, then, to scrounge for a handful of seaworthy logs, and the hemps and grasses with which to bind them. Gralok followed suit.

In time, and with the aid of the small war-axe they'd brought along, they'd hewn six suitable pieces of timber to comparable lengths. Then, with their impromptu twine -- and with the bit of rope that had been included in their packs -- they were able to begin fashioning. Balgor chose the lightest, most buoyant woods for the project, particularly several partially-rotted trunks, for he'd determined that with his and Gralok's combined hefts they would need to displace as little water as possible to stay afloat. Decaying wood weighed less, and would therefore trim a few grams in the right direction. And although he knew that the rotted lengths would waterlog more quickly than would haler ones, he believed that they would nevertheless serve nicely for two short jaunts -- one to Orlahn, one from.

Another little gem of sailing ad hockery that he'd learned from one of the more knowledgeable fishermen in the rebel camp was to employ longer pieces of timber in the construction -- longer than what seemed sensible -- as he was assured that this would not only spread the load across a greater surface, but it would make the raft easier to manoeuvre. Neither man being at all nautical, they truly did not know what to expect once asea; but they were not the kind to shrink from new challenge, especially when the realm stood in the balance.

For the sake of convenience, they built the raft while standing knee-deep in the water, even as many an ornery comber jostled their efforts with irking regularity. The bobbing logs, however, weren't tossed to quite the extreme that they might have been -- and in fact rode the surface rather splendidly -- which made for a less harrowing process in securing them one to the other. And eventually, beyond a few false starts, one failed twine, and a peck of re-work, they had before them a not-so-handsome but workable conveyance for bringing them to the people of Orlahn.

Oars were next, and they spent an inordinate time in search of suitable paddle-wood. Nothing at hand seemed broad enough to provide for efficient stroking, and neither man understandably wished to hack and hew at a large trunk in hopes of netting the wide, sturdy, slim-handled accessory that they desired. At end, however, they were forced to do just that. Driving both the axe and their daggers into what was deemed the most promising bole, with considerable effort they were able to wedge in and split it lengthwise, which yielded them a radial pair, each with one flat side. Then, going to work on the barked portions of the halves, they whittled and carved and excised until they had resected enough to result in two passable oars.

Petulant in their success, within minutes of completion they redonned their packs, refitted themselves, and made ready to fulfil their mission. Leaving solidity and sure-footed comfort behind, they pushed off with the confidence of fools, hopeful that their amateur construct would be sturdy enough to see them through.

Far from a blustery day, upon the water it soon became a different story. Once they were fully committed the wind gained advantage, and at times it was more than they could manage merely to balance the craft and keep its heading straight. But they were strong men, and persistent, and after escaping the influence of the shore-bound breakers it became easier to maintain their bearing, windy or not. One man paddling from the port side, and the other, from starboard, they proceeded without falter or incident toward the misty isle ahead.

At roughly two kilometres out, however, near the half-way point, something in the water caught Balgor's eye. In silhouette, twenty metres from the bow, there appeared an object in jut from the surface. As quickly as he focused on it, it submerged and was replaced by two similar juts ten and fifteen metres to starboard. He called Gralok's attention to the phenomenon, but he, of course, had seen nothing. The pair of silhouettes having slipped beneath the water no less swiftly than the first, it was only when all three bobbed up simultaneously a few seconds later that each man saw what the other did.

"Men or fish?" asked Gralok.

"I know not. My only hope is that they are one or the other, and not something that is neither man nor fish."

"What could be neither man nor fish? Sea-faring vrohdas?"

"Jest if you wish," said the realmson. "But I like it not."

They rowed on with a bit less verve in their strokes, instead channelling that cautious percentage of energy into a jerky paranoia of glances for additional signs of unwanted company.

"Why do you tap on the raft?" asked Balgor.

"It is not I," said Gralok.

Balgor touched the wood beneath him. There was definitely a vibrative sensation to it, vibrative as when mice burrowed and chewed within the walls of one's abode. Had they unknowingly chosen a log that had been host to a rodent hovel? An insect nest? No, he knew that this couldn't be; the former would have fled their pulpy sanctuary at the first few axe hacks, and the latter would surely have swarmed in defence of theirs. Yet, if not these explanations, then what?

They hadn't long to ponder. Within the minute, the outer starboard log detached from their craft and fell away in drift. Balgor grabbed for it, but his effort returned him nothing save a severed strand of twine.

"Blasted saboteurs!" cried Balgor. "They seek to undo us! Quickly, Gralok -- your blade!"

Both men drew and began jabbing their daggers through the joints and alongside the vessel, hoping to dissuade their assailants from disabling them further. Whether it was man or beast below, surely they bled, and randomly thrusted steel was the best and most that the rafters could offer in countermeasure.

This worked, temporarily. But, so busied with keeping their log-boat whole, this left no one to paddle it; and when they settled on one man defending and one man rowing, their harrowers counteracted in thwart. Apparently gleaning the position of the oar-man from underneath, said clever beings fixed upon the lashings beneath him and continued to dismantle. The rafters, frustrated by their disadvantage, rowed and stabbed, stabbed and rowed -- neither with calm or focus -- until the very moment that their submarine saboteurs finally succeeded in unseaming the construct completely.

Suddenly amid a loosed muddle of logs, each drifting in its own direction, Balgor and Gralok quickly spilled into the drink. Floundering in the bracing chill, they lashed at empty ocean, thrusting their blades wildly in a long-shot hope of crippling a far more dextrous enemy. Finding their backpacks not terribly buoyant, both men were too limited in their mobility to simultaneously fend and tread water, and it was no significant while before they began to tire. Dark, shadowy forms darted confidently around them, deliberately drawing their fruitless exertions and draining them further, and before long neither man was in condition to retaliate. And of the little fight that remained in them, this was easily expended with a bit of body-buffeting knockabout, courtesy of their still-faceless assailants.

Groggy, almost drunkenly so, Balgor drifted between windedness and exasperation. He felt his body in bob within the lull and pull of the tide. He barely reacted to the collective nudges that propelled him forward. He even thought nothing of it when his dagger slipped sleepily from his hand and sank to the bottom. He only knew that he and Gralok had been defeated before they'd even had a chance to serve the realm. In his past, he'd battled scores of NuRac minions and triumphed. He'd survived the Great Arena through challenge after challenge of unmeasured peril. He'd helped to orchestrate and execute the most ambitious prison escape that anyone had ever conceived. But here, now, he'd gone down with barely an effort. And even in the stupor of his exhaustion, he felt ashamed.

What? You want more? Okay, one more snippet:

From Chapter Four:

Although Wagner eschewed the pre-disembarkment gathering -- where the questers toasted swift-footed luck to one another -- he found that he could not escape ceremonial well-wishing entirely. His provisions packed, his sword frogged, and his new quarter-staff ready to aid him in anchoring his footfalls over the predictably treacherous terrain, he nevertheless found himself cornered in his humble encampment by the two women he couldn't wave aside: Ponahr of the Orb and Gamühr the Bard.

Motherly figures both, high matrons of their crafts, that they had sought Wagner out in unison spoke much to their likened esteem for him. That they were there to present him with self-crafted travellers' tokens said equally as much of their hopes for his success.

"What's this?" Wagner asked as Ponahr handed him a macramé fistlet.

"Here," she said, "slip your rough-knuckled fingers through this, Voknor, and cinch it to your wrist."

Wagner extended his hand half-heartedly as she fitted it for him.

"This doesn't mean that we're engaged or anything, does it?" he said.

"Nay, Voknor -- leastwise not without a proper courtship." Firming up the fistlet, she fastened it and grinned. "Although I think that any woman who would be your mate would do better to have two good eyes, for to keep proper watch and ward on you and your reckless ways!"

She winked at him with her false eye -- her orb -- from which her epithet was coined. A one-eyed seamstress, a virtuoso in her trade, back in QieLahr she had divided her time between sewing textiles and stitching up wounded gladiators. Wagner had been one of the latter.

"Not to be rude or unappreciative, but what is this exactly?"

"Why, a felicity girt, of course!"

"A what?"

"A felicity girt!" She looked at him, almost annoyed. "Do you truly not know?"

He shrugged. She scowled.

"Aside from aiding the grip in wet weather, it is said to invite good fortune to its wearer."

Wagner signalled friendly acknowledgement, but said nothing. Then, once she'd finished fussing, he retracted and scrutinised his palm, tracing the concoction of large-looped fancywork that faintly resembled a fingerless glove in threadbare state. Turning his hand over, he noted the wafer-thin medallion affixed centrally within the weave via four crimped tangs. Stamped upon its bronzy surface was the tiny relief of a human eye -- presumably Ponahr's personal totem.

Clenching and unclenching his fist to acclimatise himself to the new accessory, Wagner gradually abandoned his scepticism. "Hmm," he remarked. "Not too shabby. Thank you, Ponahr."

"Now mine," said Gamühr, handing him a small parchment.

Curious, Wagner slowly unfolded and examined it. "Don't tell me," he said. "A story?"

"A poem. But not just any poem, Voknor. It is my first effort to render to verse an account of our bold escape from QieLahr. I penned it only this morning. Granted, it is not yet complete -- but I thought that you might find pleasure in reading it now and again upon some occasional lull in your travels."

"I can't accept this," said Wagner, forcing it back on her. "With my luck, it might inadvertently get lost or soaked or destroyed by some unforeseen circumstance. I'd never forgive myself if I --"

"Worry not, Voknor. It cannot be lost. I have committed it to memory."

"For real?"

She rolled her eyes. "What manner of tale-spinner would I be if I needed parchments and prompters to recite my own poesy?"

"Probably somewhere around my manner, I reckon."

"Come now, Voknor -- we both know that to be false! Do you not recall your 'Icarus' narrative of several months back? You fully proved your competence as a storier that day."

"That flimsy yarn? That, my dear woman, was what you call the product of an orator's desperation. Put on the spot in front of all those people, I had to come up with something. My hands were kinda tied. And not by any felicity girt, either."

Both women scoffed at him.

"Regardless," said Gamühr, "You need not fear its loss, Voknor. Rest assured, I will retain every verse, up here, in my head."

"If you say so," said Wagner, still doubtful but nevertheless slipping the folded poem in with his provisions. "I'll save it for some weary day's end, when I'm fed and full and fire-warmed -- and ready to be eased into the night by your eloquent and dulcet inspiration."

She smiled smug satisfaction. Wagner smiled back. He hadn't the heart to tell her that he could barely read one word of Ergosian.

Motherly figures both, high matrons of their crafts, that they had sought Wagner out in unison spoke much to their likened esteem for him. That they were there to present him with self-crafted travellers' tokens said equally as much of their hopes for his success.

"What's this?" Wagner asked as Ponahr handed him a macramé fistlet.

"Here," she said, "slip your rough-knuckled fingers through this, Voknor, and cinch it to your wrist."

Wagner extended his hand half-heartedly as she fitted it for him.

"This doesn't mean that we're engaged or anything, does it?" he said.

"Nay, Voknor -- leastwise not without a proper courtship." Firming up the fistlet, she fastened it and grinned. "Although I think that any woman who would be your mate would do better to have two good eyes, for to keep proper watch and ward on you and your reckless ways!"

She winked at him with her false eye -- her orb -- from which her epithet was coined. A one-eyed seamstress, a virtuoso in her trade, back in QieLahr she had divided her time between sewing textiles and stitching up wounded gladiators. Wagner had been one of the latter.

"Not to be rude or unappreciative, but what is this exactly?"

"Why, a felicity girt, of course!"

"A what?"

"A felicity girt!" She looked at him, almost annoyed. "Do you truly not know?"

He shrugged. She scowled.

"Aside from aiding the grip in wet weather, it is said to invite good fortune to its wearer."

Wagner signalled friendly acknowledgement, but said nothing. Then, once she'd finished fussing, he retracted and scrutinised his palm, tracing the concoction of large-looped fancywork that faintly resembled a fingerless glove in threadbare state. Turning his hand over, he noted the wafer-thin medallion affixed centrally within the weave via four crimped tangs. Stamped upon its bronzy surface was the tiny relief of a human eye -- presumably Ponahr's personal totem.

Clenching and unclenching his fist to acclimatise himself to the new accessory, Wagner gradually abandoned his scepticism. "Hmm," he remarked. "Not too shabby. Thank you, Ponahr."

"Now mine," said Gamühr, handing him a small parchment.

Curious, Wagner slowly unfolded and examined it. "Don't tell me," he said. "A story?"

"A poem. But not just any poem, Voknor. It is my first effort to render to verse an account of our bold escape from QieLahr. I penned it only this morning. Granted, it is not yet complete -- but I thought that you might find pleasure in reading it now and again upon some occasional lull in your travels."

"I can't accept this," said Wagner, forcing it back on her. "With my luck, it might inadvertently get lost or soaked or destroyed by some unforeseen circumstance. I'd never forgive myself if I --"

"Worry not, Voknor. It cannot be lost. I have committed it to memory."

"For real?"

She rolled her eyes. "What manner of tale-spinner would I be if I needed parchments and prompters to recite my own poesy?"

"Probably somewhere around my manner, I reckon."

"Come now, Voknor -- we both know that to be false! Do you not recall your 'Icarus' narrative of several months back? You fully proved your competence as a storier that day."

"That flimsy yarn? That, my dear woman, was what you call the product of an orator's desperation. Put on the spot in front of all those people, I had to come up with something. My hands were kinda tied. And not by any felicity girt, either."

Both women scoffed at him.

"Regardless," said Gamühr, "You need not fear its loss, Voknor. Rest assured, I will retain every verse, up here, in my head."

"If you say so," said Wagner, still doubtful but nevertheless slipping the folded poem in with his provisions. "I'll save it for some weary day's end, when I'm fed and full and fire-warmed -- and ready to be eased into the night by your eloquent and dulcet inspiration."

She smiled smug satisfaction. Wagner smiled back. He hadn't the heart to tell her that he could barely read one word of Ergosian.

While Book Two has been delayed a few dozen times already, it's not truly because of inherent laziness or writer's block. Yes, I have been known to be slothful at times, but I rarely come up against any blockades that squelch my ideas. I do generally encounter other types of hindrances that keep me from writing and make it easier not to produce work. Back in my college days, I almost always waited to write my term papers until the last minute, no matter what I may have planned. That's likely part of the case here. Plus, as Book One was not discovered by more than a handful of readers, I had to sit down and debate as to whether anyone actually wants to see more. I see people reading mass-produced crap all the time, and that discourages writers like me who choose the proverbial road less travelled. So, as Book Two is still a Vofspar's handful of chapters from completion, I can tell you this: if you stay with me, you'll see new characters and cultures introduced, some of your favourite original characters fleshed out, and a few dozen twists and dicey predicaments to delight the intellect. That's a promise!

In addition to the two passages above, please read ahead to hear about a few non-spoiling details that will be part of Book Two:

Readers will finally get to experience some graphic scenes with the much alluded-to night hounds -- the nocturnal, glowing-eyed beasties that prowl the forests in malefic packs from dusk until dawn. These vile little nasties were mentioned -- but never seen -- in OSAS, mostly because the forest travellers (whether Ergosian or NuRac) were amply cautious in setting up the proper repellents every night. Watch for a touch of preventative laxity in Book Two, which will not only allow for the hounds to appear, but to wreak a bit of havoc.

The remote Ergosian clan known as the Chahnuk will make its debut in Book Two. The Chahnuk (mentioned in Chapter Twenty-One of OSAS) dwell in a unique and densely wooded portion of the realm, well beyond NuRac territory, where the trees not only appear dimensionally identical to the outside observer, but in standing almost perfectly equidistant from one another they create a disorienting and disquieting symmetry to the unprepared traveller who forges too quickly within.

The Isle of Orlahn and its insular Ergosian inhabitants will play a role in the events of Book Two. If the reader recalls, there were several Orlahnian prisoners imprisoned at QieLahr, most notably a man called Vonleor who, during Wagner's and Balgor's escape, earned Tamek's rebuke -- and then, his rarely offered apology (in Chapter Fifteen of OSAS).

Learn about some of the new characters from Of Quests and Quandaries on the "Characters" page!

The Koboldic Mountains: it is said that upon these three peaks dwell the mysterious kobolds, fierce gargoyles against whom no weapon can strike or draw blood. Two questers will encounter them in battle... but will they walk away unscathed?

Some of you may have noticed that I waffled a bit on the working title for Book Two. Of Quests and Quandaries has always been my original choice, but when an internet search turned up at least one other work with that name, I had to think twice. Although titles of novels generally cannot be copyrighted, I still went about plugging in other words -- a tough endeavour when you're working with Qs, let me tell you! -- since I'm not one to borrow trouble or step on other authors' tootsies. I tried the variations Of Quests and Quislings and Of Quests and Quiddities, but have finally come back to the original, mostly because I prefer it, but also because of my being haplessly prolix and word-snooty already (I like to use unusual and/or archaic terminolgy -- as if you had to be told...), which has my friends butting in and insisting that I shouldn't turn off any more potential readers with another bewildering title. So be it!